Every journey is about experiences and emotions. With one comes the other. And it all starts with one emotion so intense that you just have to give in to it. Wanderlust.

Wanderlust Travel Stories is a text-based travel game set in the real world.

Emotional Stories. They are driven by hope and curiosity, the search for love, and the need to deal with grief—an idealistic student, a jaded reporter, a man who has never traveled before. Walk with them, shape their paths, and see the world through their eyes.

Immersive Travels. From the mysterious statues of Rapa Nui, through the bustling streets of Bangkok and the vast, pristine expanses of the Antarctic, to the grasslands of the Serengeti, explore places you might never see and examine your feelings toward the places you know.

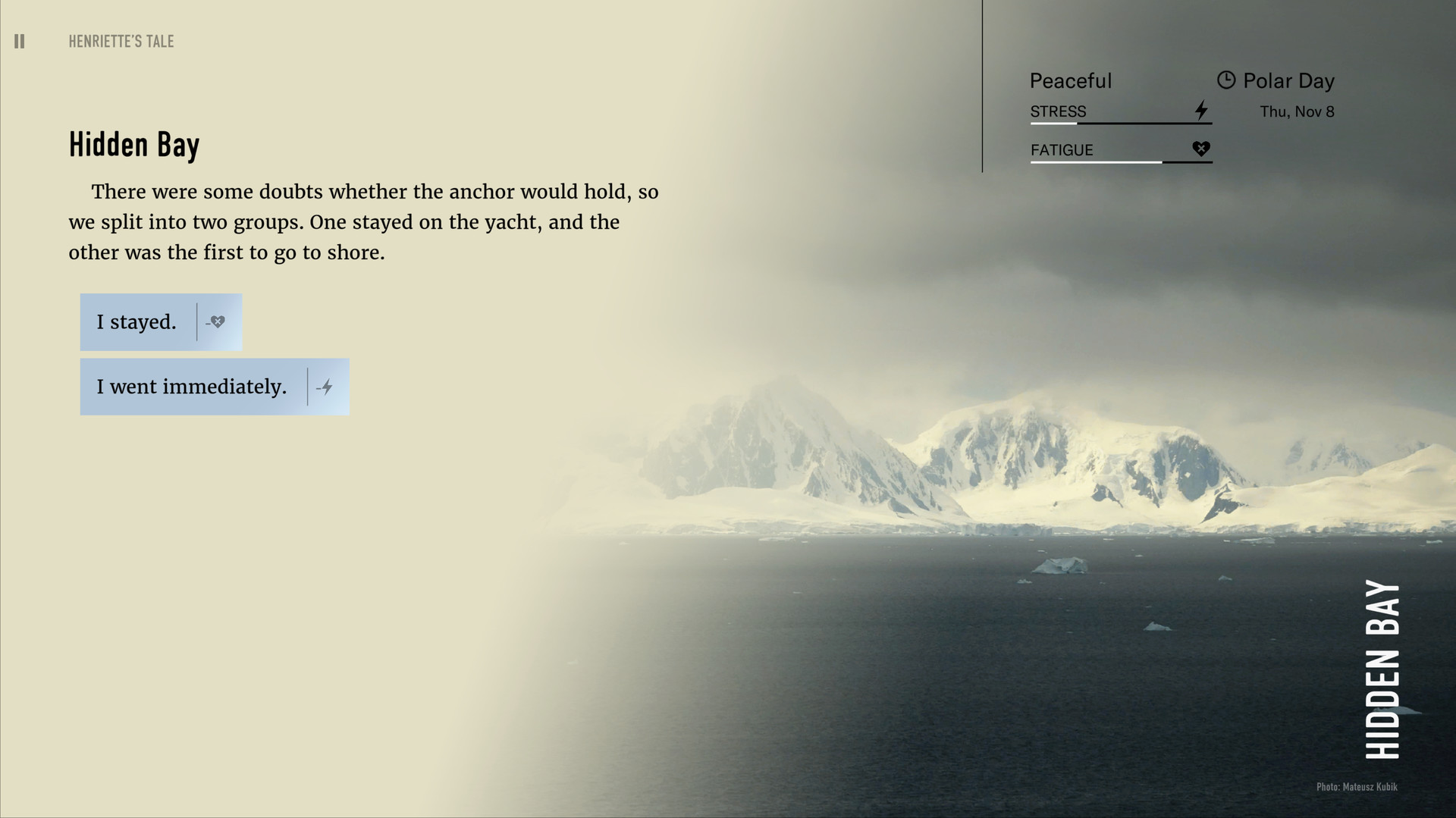

Personalized Experience. There are many things to consider: what to pack, when to leave, where to stay. Be careful to manage your stress and fatigue, because they change the way you see the world. Create a journey of your own with every choice you make.

Real Stories, Real World. Wanderlust was created by a team of travelers, journalists, artists, and game makers. Inspired by real-life adventures, these stories have been illustrated with bespoke photographs taken especially for the project or selected from private archives.

Playable Documentary. With its unique mix of slice-of-life and journalism, Wanderlust touches subjects from the melting polar caps, to the impact of the tourism industry, to the universal search for the meaning of life. Take a fresh look at your notions about the world.

Slow Gaming. You don’t have to rush. You don’t have to fight. This is your journey and you decide the pace of your adventure. Relax to the calming original soundtrack. Give yourself space to think and feel. Observe how the journey changes you.

Wanderlust Travel Stories is a game and a book. Travel the world in four novels and five short stories spanning a total of over 300,000 words and 12 hours worth of reading.

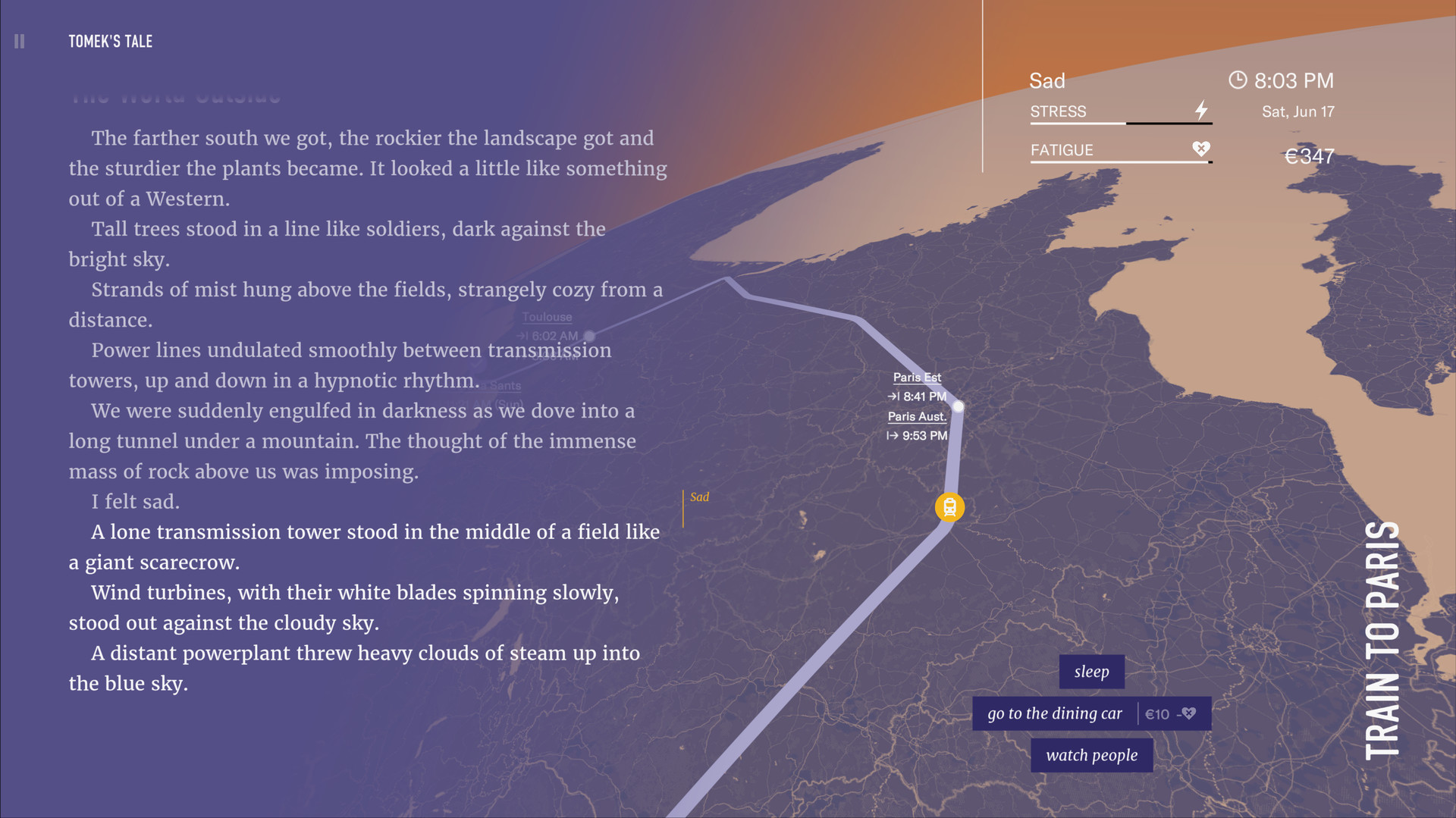

It’s Not a Love Story. He didn’t plan to be spontaneous, but it happened. Now he has to travel across all of Europe to meet a woman he doesn’t really know. His hopes are high. He might be in love. He’ll probably be late.

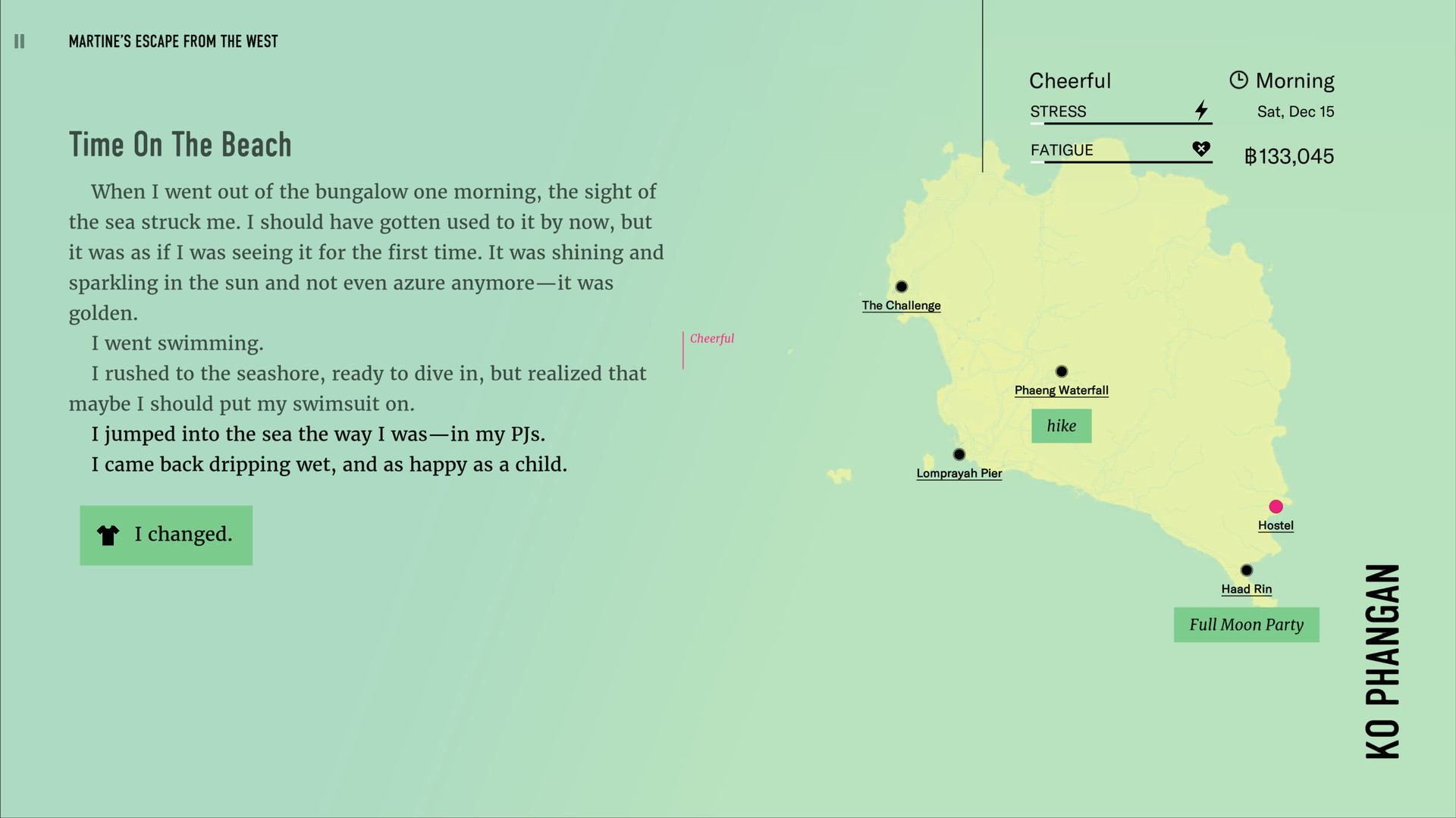

The Essential Gap Year. With every new experience, Martine has that nagging feeling that she’s changed. But is that something she needs during her perfect gap year? All she wanted was to go to Asia and find the meaning of life, just like everybody else.

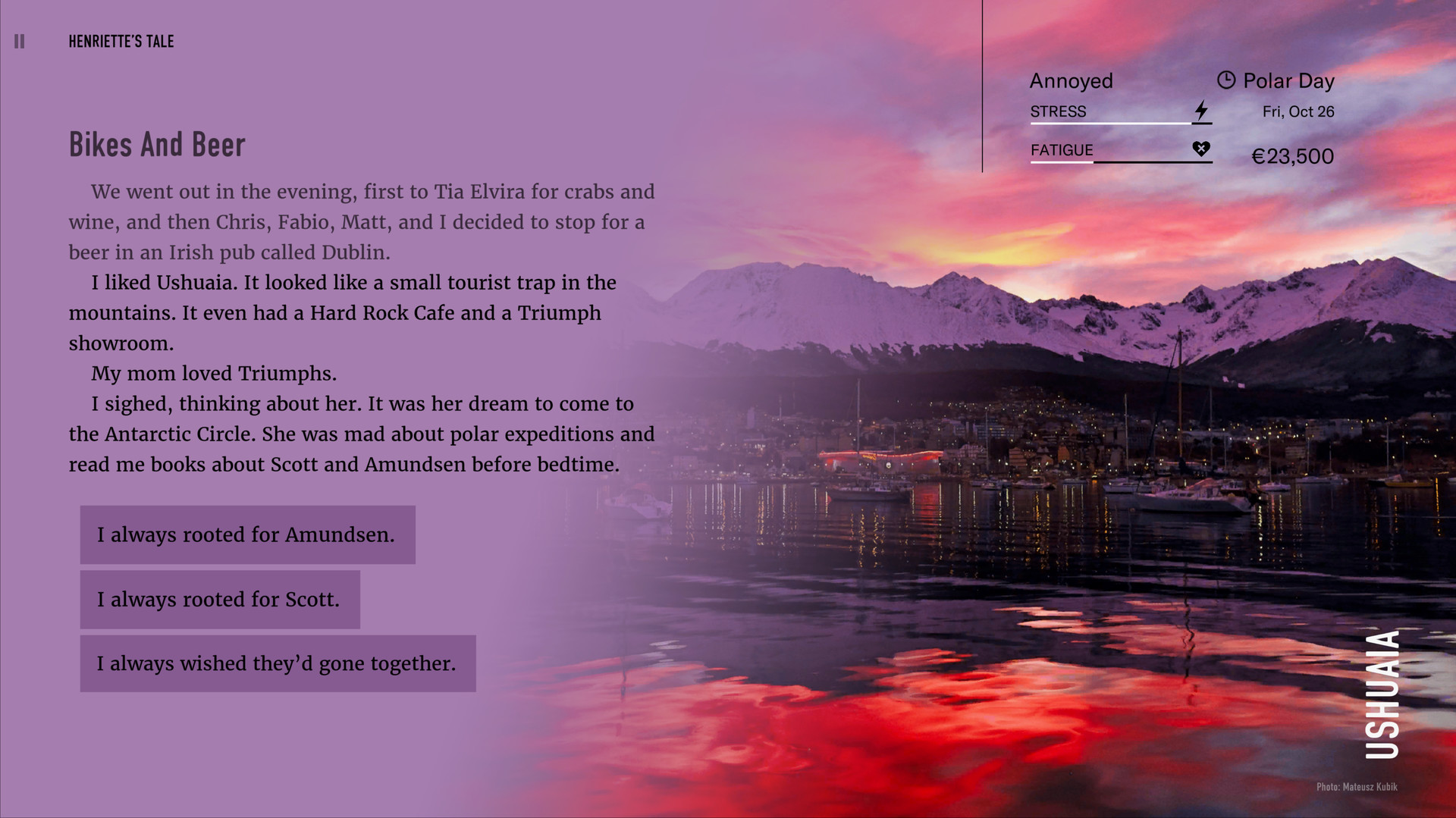

Sea Fever. Antarctica. A luxury cruiser. A yacht. A father. A daughter. Old friends. New enemies. The cold, uncaring sea.

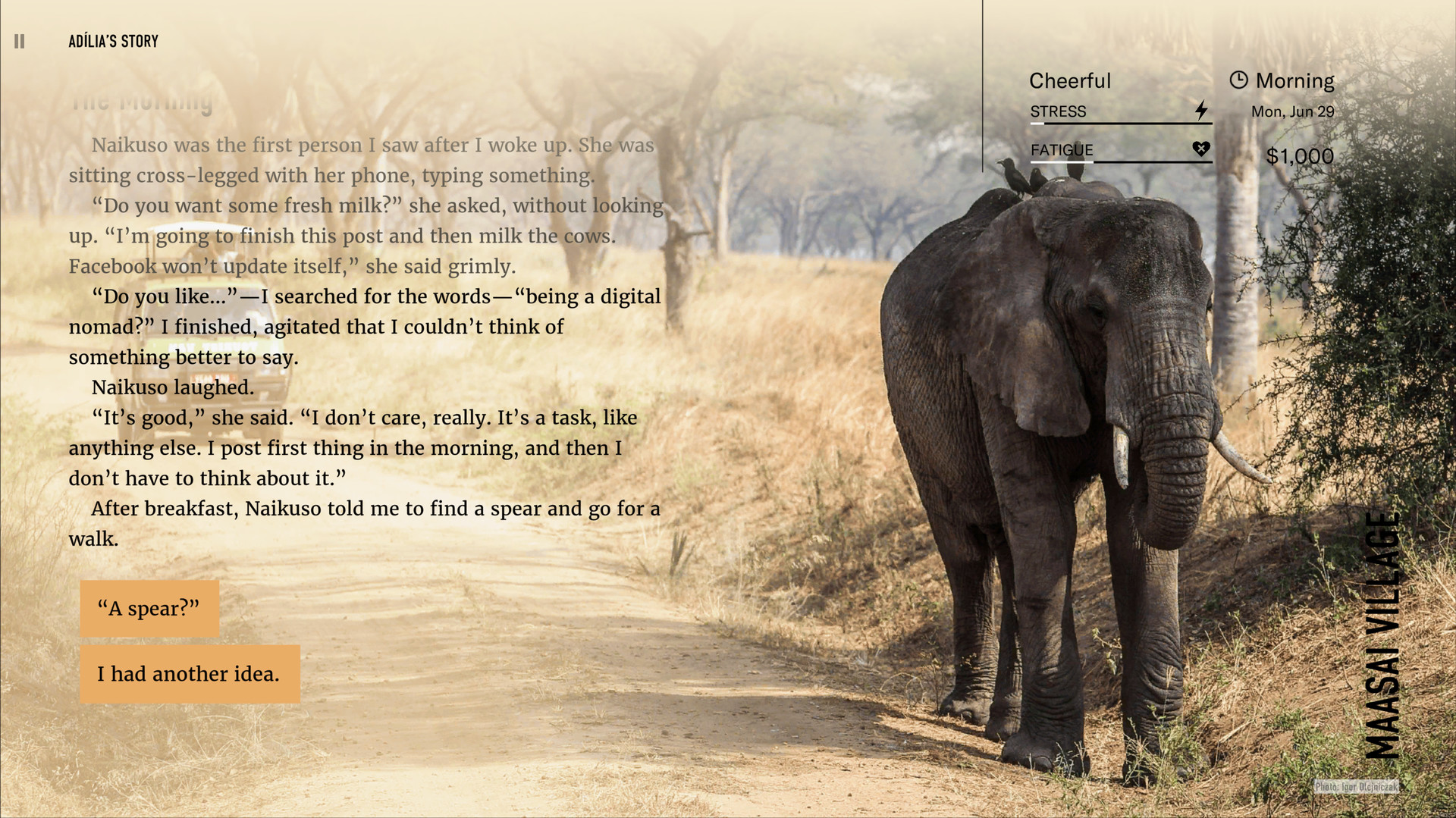

Today Is Always Gone Tomorrow. Adília felt too young for her best friend to die, too young to be fed up with her husband, and definitely too young to become a grandmother. She needed to think, to cross Africa one more time, to spend a moment alone. Six months. Maybe more. Everyone will manage while she’s gone.

Short Stories. An American circus sideshow, a rusting plane in Papua New Guinea, trolls and whales on the Faroe Islands, a sweatshop in Bangladesh—a collection of unexpected snapshots from the protagonists’ lives.

Wanderlust. A chance meeting on the world’s most remote island gets a group of tourists talking about their life journeys, their pasts and futures, their hopes and fears. With every story, passions flare and tempers rise as the travelers re-examine what they brought with them and what they left behind. Faces carved in stone watch them from the darkness.

For more travel stories follow Wanderlust on our social media channels.

(Facebook, Twitter, Instagram)

Dev Diary: Choices and Emotions

To make a game grounded in real experiences we took on board a team of travel journalists, writers, and anthropologists, and put a lot of effort into research, interviews, photographic documentation, etc. This gave us a solid framework for the story, but also limited the range of possible choices.

We wanted to show not the, sometimes boring, logistics of travel but, above all, the feelings and emotions of a traveler. To do this we constructed a cast of characters representing very different ideas about traveling and wrote a collection of stories from their personal perspectives a kind of interactive memoirs.

Wanderlust Travel Stories is a literary experience, and we made sure nothing distracts you away from the text. The static photos and illustrative soundscapes are there just to bring back memories or stir your imagination. The user interface is also very basic, its most important elements are stress, fatigue, and mood showing the emotional state of the character and its influence on the story. This mechanism is described in the next sections of this text.

What makes games unique, is that the designers set up a dilemma, but it is the player who makes the decision and is responsible for who the hero turns out to be. To make an informed choice the player has to be able to imagine possible outcomes. In well-written stories, the player can also compare the projected consequences with what really happened, and learn.

If this topic interests you, I wholeheartedly recommend John Yorkes book Into the Woods, on how the learning process in our brain coexist with and shapes the stories we tell.

That brings us to a crucial element of any decision-making process: context. Do you want a glass of water? There are two simple ways to answer, to default options: yes and no. Yet the answer would heavily depend on whether you are in a desert, dying of thirst, or on an important meeting, and really needing to go to the loo. There are moments when the context is everything.

So, we decided to highlight the subjective and personal nature of travel, to modify and multiply rather the contexts than the options. To do this, we reached for emotions.

Wanting to show how stress and fatigue influence how we feel about the places we visit, we implemented a very simple emotional simulator. It was based on a model described in Christophe Andrs book about moods called Les tats dme : Un apprentissage de la srnit.

We simplified the model a bit, and this is how it works in Wanderlust Travel Stories:

Table: stress and fatigue levels shape the character's mood

The players decisions, apart from branching the story from time to time, usually influenced stress and fatigue. The resulting mood was being fed back to the story, modifying the context of every following decision.

The idea was to have every scene opening and summary written in at least three (up to nine) versions, reflecting the characters possible moods. The more important the scene was to the main story arc, the higher emotional fidelity it had. Additionally, some options were available only in certain moods. We did not always manage to do that, but that was what we aimed for.

The way players approach the available options, depends on the context they were given, or at least that was the idea behind the design.

Low stress, high fatigue, mood: peaceful

When the character is peaceful, he sees Paris as it is, just another European city near a train station. The main choice in this scene is how to proceed, whether to take a taxi or walk. Because Tomek is fatigued, an extra option appears I was hungry. We can expect that most players will eat something (to regain some strength) and then decide whether to walk or call a taxi.

High stress, high fatigue, mood: hopeless

The situation changes when the character is hopeless. High stress and high fatigue render the world hostile, and the character focus on possible dangers: drunks, shouting, a reeking dumpster. The main call-a-taxi-or-walk choice remains the same, and there are two extra options: I was hungry, and I needed a drink, the later triggered by high stress. Eating is still a valid option gameplay-wise, but in the presence of a smelly dumpster, many players lose their appetite and just call a taxi to get out of that awful place.

Normal stress, normal fatigue, mood: calm

When a character is calm the place looks normal and the choice boils down to picking the best way to proceed. Curious players will probably take a walk, while the optimizers would probably call a taxi to save their strength for the future.

Low stress, normal fatigue, mood: optimistic

An optimistic character sees the city in its most glamorous form, full of light and excitement. It looks inviting, making the taxi seem like a less interesting choice.

The graph of the scene looks like this:

As far as the branching goes, the situation is quite simple we make a decision, and at the end of the scene we either walk down one branch or sit in a taxi going down another branch of the story tree. Sometimes there are extra diversions available, in the form of short scenes in a bar and/or in a bistro, but they feed back to the main choice.

But when we look at the mood-dependent contexts, the situation gets more interesting. Although the number of outcomes stays the same, the number of personal situations framing the decision multiply. Taking a taxi to escape a hostile environment is a different decision than giving up on an otherwise alluring walk to save strength for another day. A quick snack before a night stroll is something different than a forced meal in a dive near a smelly dumpster.

We learned the nuances of this technique as we went, so not all instances youll find in the game, work perfectly, but we found it a great production tool. It allowed us to save on extensive (and expensive) branching we were prone to, and to keep the story within our research-based limits, while allowing for extensive personalization of the events. We set most scenes in the mood-depending context, and as a result, the number of personal decision-making situations available to players became much higher than the actual scene count.

We used this simple and effective mechanism both to personalize small details of the stories and to decide about the outcomes of whole character arcs.

The details can be as small as whether Henriette is a tea or a coffee person. The first choice the player makes about their favorite beverage reflects on the whole long sailing to Antarctica with a steaming cup of tea (or coffee) in hand. Sometimes the changes are about people. Depending on how the player directs Adlias relation with her husband, she talks about him using his name Jose or coldly calls him the husband. The mechanism is crucial in the storys finale, when the available options that shape Adlias future, are gated by variables reflecting her relationships with various people in her life.

The solution we reached for, was to use the players decision points not only to branch the story but also to set different variables, which then fed back to the following scenes, modifying them to reflect how the player directed the character.

The most universal and crucial of the variables, were stress and fatigue, which we used to track the mood of the characters. The mood then influenced how surroundings were described, providing changing and personal context for every decision. Thanks to this, using a limited number of story branching points, we aimed to create a significantly higher number of unique decision situations.

We learned how to use the mechanisms as the production progressed, so the implementation is not always perfect, but we believed the idea was interesting enough to share it with you.

I hope you'd find this look behind the scenes worth your time.

Our Goals

In May 2018 we decided to make a story game about travel. We wanted to keep it real, introspective and minimalistic.To make a game grounded in real experiences we took on board a team of travel journalists, writers, and anthropologists, and put a lot of effort into research, interviews, photographic documentation, etc. This gave us a solid framework for the story, but also limited the range of possible choices.

We wanted to show not the, sometimes boring, logistics of travel but, above all, the feelings and emotions of a traveler. To do this we constructed a cast of characters representing very different ideas about traveling and wrote a collection of stories from their personal perspectives a kind of interactive memoirs.

Wanderlust Travel Stories is a literary experience, and we made sure nothing distracts you away from the text. The static photos and illustrative soundscapes are there just to bring back memories or stir your imagination. The user interface is also very basic, its most important elements are stress, fatigue, and mood showing the emotional state of the character and its influence on the story. This mechanism is described in the next sections of this text.

On Decisions

In the heart of every good scene is a dilemma the hero must face. By observing the hero in action we learn who they really are. The action changes the situation and creates consequences, often resulting in another dilemma.What makes games unique, is that the designers set up a dilemma, but it is the player who makes the decision and is responsible for who the hero turns out to be. To make an informed choice the player has to be able to imagine possible outcomes. In well-written stories, the player can also compare the projected consequences with what really happened, and learn.

If this topic interests you, I wholeheartedly recommend John Yorkes book Into the Woods, on how the learning process in our brain coexist with and shapes the stories we tell.

On Context

If we stick to the above-mentioned rules, every scene should include such elements:- setting the dilemma,

- presenting options,

- decision,

- delivering consequences.

That brings us to a crucial element of any decision-making process: context. Do you want a glass of water? There are two simple ways to answer, to default options: yes and no. Yet the answer would heavily depend on whether you are in a desert, dying of thirst, or on an important meeting, and really needing to go to the loo. There are moments when the context is everything.

So, we decided to highlight the subjective and personal nature of travel, to modify and multiply rather the contexts than the options. To do this, we reached for emotions.

On Emotions

As many travelers would tell you, sometimes the world is what it is, but usually emotions color the perception. When tired or stressed you experience the world differently.Wanting to show how stress and fatigue influence how we feel about the places we visit, we implemented a very simple emotional simulator. It was based on a model described in Christophe Andrs book about moods called Les tats dme : Un apprentissage de la srnit.

We simplified the model a bit, and this is how it works in Wanderlust Travel Stories:

Table: stress and fatigue levels shape the character's mood

The players decisions, apart from branching the story from time to time, usually influenced stress and fatigue. The resulting mood was being fed back to the story, modifying the context of every following decision.

The idea was to have every scene opening and summary written in at least three (up to nine) versions, reflecting the characters possible moods. The more important the scene was to the main story arc, the higher emotional fidelity it had. Additionally, some options were available only in certain moods. We did not always manage to do that, but that was what we aimed for.

Case Study: One Night in Paris

As an example, I chose a scene in Paris, one that is not spoilery and designed well enough to dissect in the public. Our hero steps off the train and has his first experience with the capital of France. What he sees and what options are available depends on his stress and fatigue.The way players approach the available options, depends on the context they were given, or at least that was the idea behind the design.

Low stress, high fatigue, mood: peaceful

When the character is peaceful, he sees Paris as it is, just another European city near a train station. The main choice in this scene is how to proceed, whether to take a taxi or walk. Because Tomek is fatigued, an extra option appears I was hungry. We can expect that most players will eat something (to regain some strength) and then decide whether to walk or call a taxi.

High stress, high fatigue, mood: hopeless

The situation changes when the character is hopeless. High stress and high fatigue render the world hostile, and the character focus on possible dangers: drunks, shouting, a reeking dumpster. The main call-a-taxi-or-walk choice remains the same, and there are two extra options: I was hungry, and I needed a drink, the later triggered by high stress. Eating is still a valid option gameplay-wise, but in the presence of a smelly dumpster, many players lose their appetite and just call a taxi to get out of that awful place.

Normal stress, normal fatigue, mood: calm

When a character is calm the place looks normal and the choice boils down to picking the best way to proceed. Curious players will probably take a walk, while the optimizers would probably call a taxi to save their strength for the future.

Low stress, normal fatigue, mood: optimistic

An optimistic character sees the city in its most glamorous form, full of light and excitement. It looks inviting, making the taxi seem like a less interesting choice.

The graph of the scene looks like this:

As far as the branching goes, the situation is quite simple we make a decision, and at the end of the scene we either walk down one branch or sit in a taxi going down another branch of the story tree. Sometimes there are extra diversions available, in the form of short scenes in a bar and/or in a bistro, but they feed back to the main choice.

But when we look at the mood-dependent contexts, the situation gets more interesting. Although the number of outcomes stays the same, the number of personal situations framing the decision multiply. Taking a taxi to escape a hostile environment is a different decision than giving up on an otherwise alluring walk to save strength for another day. A quick snack before a night stroll is something different than a forced meal in a dive near a smelly dumpster.

We learned the nuances of this technique as we went, so not all instances youll find in the game, work perfectly, but we found it a great production tool. It allowed us to save on extensive (and expensive) branching we were prone to, and to keep the story within our research-based limits, while allowing for extensive personalization of the events. We set most scenes in the mood-depending context, and as a result, the number of personal decision-making situations available to players became much higher than the actual scene count.

On Personalization

The mood simulator was just a specific, and the most universal, case when we used variables to personalize the story. In short, it worked like this: the main decision in a scene branched the story, but some of the decisions also changed a variable value (be it fatigue, the strength of a relationship with another character, or just noting that a certain event took place). The variable then fed back to scenes down the story-tree, no matter which of the branches we explored.We used this simple and effective mechanism both to personalize small details of the stories and to decide about the outcomes of whole character arcs.

The details can be as small as whether Henriette is a tea or a coffee person. The first choice the player makes about their favorite beverage reflects on the whole long sailing to Antarctica with a steaming cup of tea (or coffee) in hand. Sometimes the changes are about people. Depending on how the player directs Adlias relation with her husband, she talks about him using his name Jose or coldly calls him the husband. The mechanism is crucial in the storys finale, when the available options that shape Adlias future, are gated by variables reflecting her relationships with various people in her life.

Looking Back

We wanted to tell stories that were real and personal, and we knew that we would be working in a small team and within the limits set by our research. Those factors advised against extensive branching of the story (which was our first idea), yet we wanted to keep the experience varied among different players, and we wanted it to feel personal.The solution we reached for, was to use the players decision points not only to branch the story but also to set different variables, which then fed back to the following scenes, modifying them to reflect how the player directed the character.

The most universal and crucial of the variables, were stress and fatigue, which we used to track the mood of the characters. The mood then influenced how surroundings were described, providing changing and personal context for every decision. Thanks to this, using a limited number of story branching points, we aimed to create a significantly higher number of unique decision situations.

We learned how to use the mechanisms as the production progressed, so the implementation is not always perfect, but we believed the idea was interesting enough to share it with you.

I hope you'd find this look behind the scenes worth your time.

[ 2019-12-09 14:40:25 CET ] [Original Post]

Minimum Setup

- Processor: Dual core or betterMemory: 4 GB RAM

- Memory: 4 GB RAM

- Graphics: Intel HD 4400 or better

- Storage: 2 GB available space

GAMEBILLET

[ 6421 ]

FANATICAL

[ 5869 ]

GAMERSGATE

[ 1559 ]

MacGameStore

[ 2356 ]

INDIEGALA

[ 546 ]

LOADED

[ 1040 ]

ENEBA

[ 32766 ]

Green Man Gaming Deals

[ 177 ]

FANATICAL BUNDLES

GMG BUNDLES

HUMBLE BUNDLES

INDIEGALA BUNDLES

by buying games/dlcs from affiliate links you are supporting tuxDB