Commander wanted! Construct giant robots, build an army of a thousand Fleas. Move mountains if needed. Bury the enemy at all cost!

- Traditional real time strategy with physically simulated units and projectiles.

- 100+ varied units with abilities including terrain manipulation, cloaking and jumpjets.

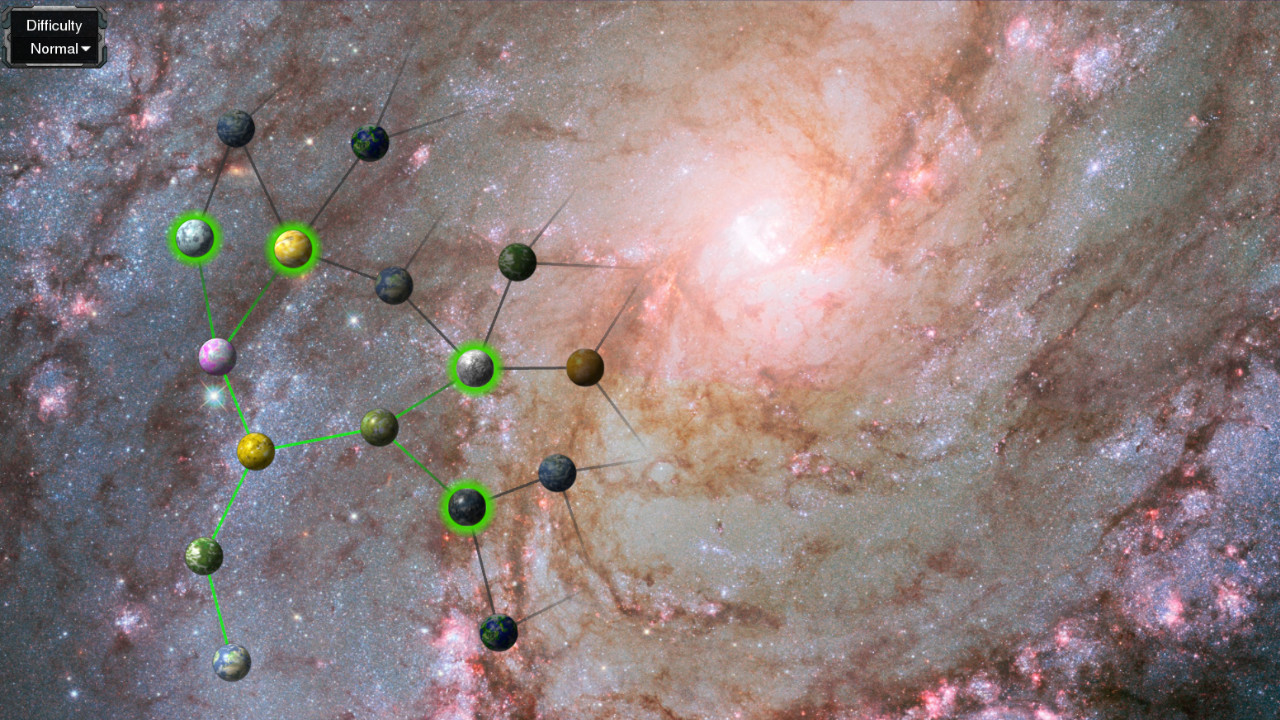

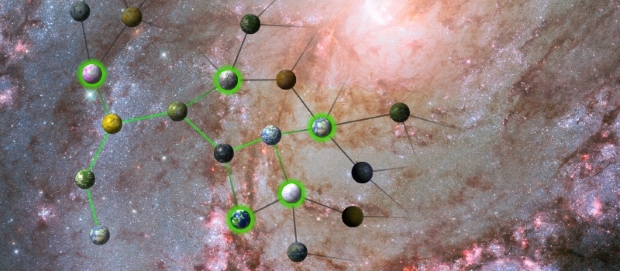

- 70+ mission galaxy-spanning campaign to be enjoyed solo or co-op with friends.

- Challenging, (non-cheating) skirmish AI and survival mode.

- Multiplayer 1v1 - 16v16, FFA, coop. ladders, replays, spectators and tournaments.

- PlanetWars - A multiplayer online campaign planned to start in May.

- Really free, no paid advantages, no unfair multiplayer.

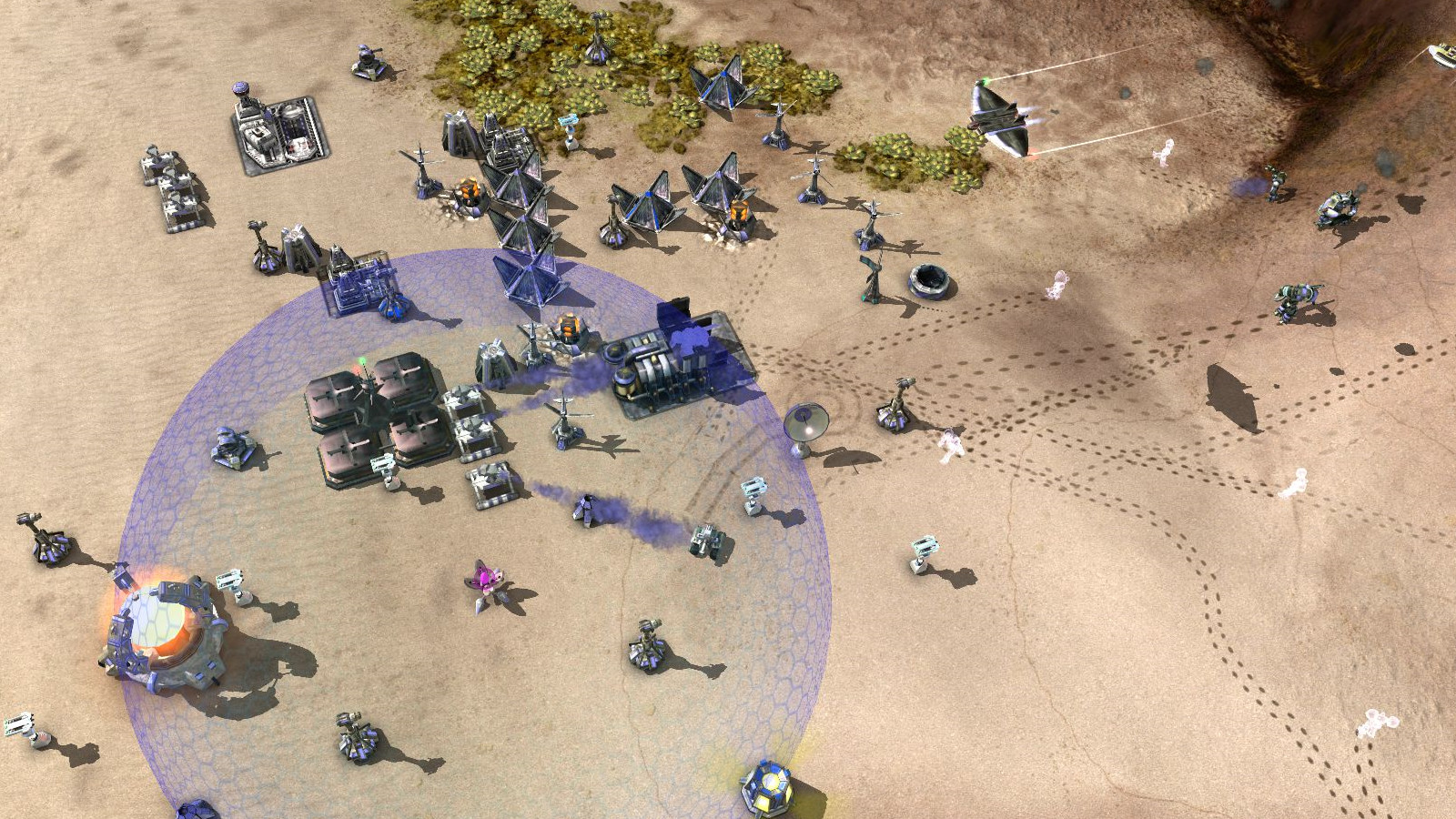

Fully Utilized Physics

Simulated unit and projectile physics is used to a level rarely found in a strategy game.

- Use small nimble units to dodge slow moving projectiles.

- Hide behind hills that block weapon fire, line of sight and radar.

- Toss units across the map with gravity guns.

- Transport a battleship to a hilltop - for greater views and gun range.

Manipulate the Terrain

The terrain itself is an ever-changing part of the battlefield.

- Wreck the battlefield with craters that bog down enemy tanks.

- Dig canals to bring your navy inland for a submarine-in-a-desert strike.

- Build ramps, bridges, entire fortress if you wish.

- Burn your portrait into continental crust using the planetary energy chisel.

Singleplayer Campaign and Challenging AI

Enjoy many hours of single player and coop fun with our campaign, wide selection of non-cheating AIs and a survival mode against an alien horde.

- Explore the galaxy and discover technologies in our singleplayer campaign.

- Face a challenging AI that is neither brain-dead nor a clairvoyant cheater.

- Have some coop fun with friends, surviving waves of chicken-monsters.

- Cloaking? Resurrection? Tough choices customizing your commander.

Casual and Competitive Multiplayer

Zero-K was built for multiplayer from the start, this is where you can end up being hooked for a decade.

- Enjoying epic scale combat? Join our 16v16 team battles!

- Looking for a common goal? Fight AIs or waves of chicken-monsters.

- Prefer dancing on a razor's edge? Play 1v1 in ladder and tournaments.

- Comebacks, betrayals, emotions always running high in FFA.

- Want to fight for a bigger cause? Join PlanetWars, a competitive online campaign with web-game strategic elements, diplomacy and backstabbing (currently on hiatus pending an overhaul).

Power to the People

We are RTS players at heart, we work for nobody. We gave ourselves the tools we always wanted to have in a game.

- Do what you want. No limits to camera, queue or level of control.

- Paint a shape, any shape, and units will move to assume your formation.

- Construction priorities let your builders work more efficiently.

- Don't want to be tied down managing every unit movement? Order units to smartly kite, strafe or zig zag bullets.

Plenty of Stuff to Explore (and Explode)

Zero-K is a long term project and it shows, millions hours of proper multiplayer testing and dozens of people contributing ever expanding content.

- Learn to use all of our 100+ units and play on hundreds of maps.

- Invent the next mad team-tactics to shock enemies and make allies laugh.

- Combine cloaking, teleports, shields, jumpjets, EMP, napalm, gravity guns, black hole launchers, mind control and self-replication.

- Tiny flea swarm that clings to walls?

- Jumping "cans" with steam-spike?

- Buoys that hide under water to ambush ships?

- Mechs that spew fire and enjoy being tossed from air transports?

- Carrier with cute helicopters?

- Jumping Jugglenaut with dual wielding gravity guns?

- Meet them in Zero-K!

The Huge Graphics Update of last week was a huge success and only introduced a few minor issues. This update fixes the ones that we are aware of.\n

- \n

- Fixed a texture detail issue that made units slightly pixelated and a bit harder to distinguish at medium zoom levels.\n

- Tweaked outlines to be a bit more visible when zoomed out, by default.\n

- Fixed status effects clipping into undamaged nanoframes. The status effect shader thought that nanoframes should be deformed, but they are not.\n

- Fixed grid hotkeys missing from most build menus.\n

- Added Colemak keyboard layout preset (thanks allentiak).\n

- Factories now open automatically when completed.\n

- Amph and Spider now have to wait 1s to open before starting production, to match other factories.\n

- Fixed the lighting on a few more maps.\n

This update overhauls the tech behind drawing units, wrecks and map features on your screen. This has many advantages. To start with, it allows for more and better looking fancy unit rendering effects, many of which are showcased in gif form below. It should also be less performance hungry on most hardware since it makes much more use of the GPU.\n\nThe deeper impact is that the new tech (physically based rendering) gives artists more tools to make units look even better. Tweaking textures to work with the new tech is an ongoing process, and one that would be much improved by the help of a volunteer artist or two. Another task is that of improving the lighting on many maps. Units are now more responsive to the sun, and tweaking it is just a matter of moving a few sliders around.\n\nMost of this work builds on efforts within BAR to push the visuals of the engine forwards, with special thanks to ivand and FLOZi for assistance with adapting and improving it for Zero-K. We also want to thank the testers and contributors that helped add features and find technical issues prior to release. Finally, thanks 64-Bit Dragon for putting together the video below.\n \n\n

Visuals

\n\n \nNew and improved status effects!\n\n

\nNew and improved status effects!\n\n

\nFancy nanoframes and swaying trees! The nanoframes are highlighted near 99.9% to make abandoned construction harder to overlook.\n\n

\nFancy nanoframes and swaying trees! The nanoframes are highlighted near 99.9% to make abandoned construction harder to overlook.\n\n \nUnits start getting wrecked before they die!\n\n

\nUnits start getting wrecked before they die!\n\n \nTrails for pew-pew lasers (thanks Thorneel)!\n\n

\nTrails for pew-pew lasers (thanks Thorneel)!\n\n \nNew cloak effects!\n\n

\nNew cloak effects!\n\n \nRelatively modern physically based rendering to expand the artistic palette!\n\nAlso:

\nRelatively modern physically based rendering to expand the artistic palette!\n\nAlso:- \n

- Units cast shade on each other.\n

- Boosted contrast adaptive sharpen slightly.\n

- Toned down bloom.\n

- Disabled screen space ambient occlusion by default as it is not worth the performance cost.\n

- Adjusted the textures of many units and the lighting on many maps, but there is still more to do.\n

Features

\n\n- \n

- Improved the radar shadow preview widget and enabled it by default. It is now more accurate (thanks Helwor) and takes structure terraform into account.\n

- Units stop and wait when a nearby friendly transport tries to pick them up.\n

- Constructors in friendly transports are considered idle when the transport is idle, and pressing the idle constructor button selects the transport (thanks strategineer).\n

- Constructors in enemy transports are no longer considered idle (thanks strategineer).\n

- The idle constructor button flashes briefly when a new constructor becomes idle, configurable under \"Settings/HUD Panels/Quick Selection Bar\" (thanks strategineer).\n

- Added tooltips for endgame awards (thanks strategineer).\n

- Factories no longer inherit the retreat state of their builder by default.\n

- Added maximum zoom option to the COFC camera (thanks therxyy and kcin).\n

- Added clickthrough settings for the command panel and quick selection bar, found in \"Settings/HUD Panels\" (thanks strategineer).\n

- Added an option to show unit icon on the command panel, found in \"Settings/HUD Panels/Command Panel\" (thanks strategineer).\n

- Added Workman keyboard layout preset, found in \"Hotkeys/Grid Hotkeys\" (thanks strategineer).\n

- Tidal generator placement no longer uses the wind icon to denote income (thanks strategineer).\n

- Made it harder to unwittingly disable shaders in lobby settings.\n

Mapping and Modding

\n\n- \n

- Units and map features can be given normal maps by setting customParams.normaltex. Eg normaltex = \"unittextures/bomberheavy_normals.dds\".\n

- Model tex2 is now interpreted as a PBR texture. Red is emissivity (for lights and engines), green is metalicness, and blue is roughness.\n

- Unit textures can now be overridden with customParams.override_tex1 and customParams.override_tex2. Eg override_tex2 = \"unittextures/m1r0.dds\".\n

- Shielded units can set customParams.shield_fxs_type = \"chicken\" to render a chicken shield (thanks XNTEABDSC).\n

- Added a toggle for the metal spot placer mapping tool to Settings/Toolbox.\n

- The startbox editor now has a tooltip that tells you where it the startbox file.\n

- Added a tickbox under \"Settings/Graphics/Sun, Fog & Water\" to set a default sun angle and pitch.\n

- Developer mode detection also looks for devmode.txt.txt.\n

Fixes

\n\n- \n

- Hacksaw no longer wiggles around while under construction.\n

- Non-line jump commands to groups of units now only spread units to passable terrain.\n

- Fixed slightly misapplied Ronin texture (thanks garfild888).\n

- Fixed Gnat gun being slightly detatched from its body. (thanks garfild888).\n

- Fixed unit information window crash on Funnelweb space click.\n

- Fixed Mace sometimes having trouble leaving the factory.\n

- Fixed Duck range not resetting properly when exiting deep water (thanks strategineer).\n

- Removed excess technical details from unit spotter markers on AI units (thanks strategineer).\n

- Fixed resource bar text truncation with large font sizes (thanks strategineer).\n

- Shifted the default garbage collection rate more towards stability.\n

- Removed leftover terraform points on planet Ungtaint.\n

Shield generators are a mainstay of sci-fi across mediums, and RTS is no exception. Games tend to use shields as an extra type of hitpoints, one that tends to have some advantage or is at least easier to replenish. They also make for great eye candy. So it is weird that Total Annihilation lacks shields, and understandable that almost every game it spawned includes them. Even TA modders got in on the action, although reportedly the shields were quite laggy as they reused the nuke interception system. Zero-K uses shields both in close quarters combat and as defence against long ranged artillery.\n\nVery long-time players, or just those with some knowledge of BAR, may be wondering why Zero-K shields are hard shells, when instead they could be bouncing projectiles all over the place. This is a weirdly specific question to everyone else, but it makes sense in light of the history of Spring, the underlying engine. The default shields were repulsion shields, and while they are unlikely to make a comeback, their removal was a great test-bed for a slew of principles that came to define Zero-K design.\n\n \n\nShield support was added to Spring in 2005 by SJ, back when the engine was the experimental playground, as Lua scripting was yet to be added. Not to be outdone by the future wackiness of Complete Annihilation , these shields repelled projectiles, with the Zero-K hard-shell version only being added later. Repulsion shields were taken up by the TA-derived mods, primarily as a defence against late-game Big Bertha spam, and 20 years later this is still their role in BAR. But Complete Annihilation, and later Zero-K, was very much about pushing mechanics as far as they can go, and damage mitigation opens up too many possibilities to be left to languish in a corner of the game. Besides, the narrow late-game linchpin role was superbly filled by nuke and antinuke , so we set out to integrate shields into the rest of the game. We succeeded, but had to drop repulsion as a result.\n\nRepulsion shields were fun, and it was sad to lose them, but ultimately they were unworkable. To start with, blocking plasma cannons while allowing everything else through felt too arbitrary. Consider Glaive and Bandit: both are light raiders, but one shoots plasma while the other has a laser blaster. This caused plasma repulsion to theoretically counter Glaive and not Bandit, but this was fine in prior games since raiders were obsolete by the time shields showed up. We could have designed around this counter relationship, and the missile defence lasers in C&C: Generals are an example of this, but doing so imposes a lot of design constraints. By this point we had plenty of constraints, and a diverse set of weapons designed with them in mind, so adding a hard counter would have destroyed much of what we had built. The result is that our new shields had to interact with all types of weapon.\n\n

\n\nShield support was added to Spring in 2005 by SJ, back when the engine was the experimental playground, as Lua scripting was yet to be added. Not to be outdone by the future wackiness of Complete Annihilation , these shields repelled projectiles, with the Zero-K hard-shell version only being added later. Repulsion shields were taken up by the TA-derived mods, primarily as a defence against late-game Big Bertha spam, and 20 years later this is still their role in BAR. But Complete Annihilation, and later Zero-K, was very much about pushing mechanics as far as they can go, and damage mitigation opens up too many possibilities to be left to languish in a corner of the game. Besides, the narrow late-game linchpin role was superbly filled by nuke and antinuke , so we set out to integrate shields into the rest of the game. We succeeded, but had to drop repulsion as a result.\n\nRepulsion shields were fun, and it was sad to lose them, but ultimately they were unworkable. To start with, blocking plasma cannons while allowing everything else through felt too arbitrary. Consider Glaive and Bandit: both are light raiders, but one shoots plasma while the other has a laser blaster. This caused plasma repulsion to theoretically counter Glaive and not Bandit, but this was fine in prior games since raiders were obsolete by the time shields showed up. We could have designed around this counter relationship, and the missile defence lasers in C&C: Generals are an example of this, but doing so imposes a lot of design constraints. By this point we had plenty of constraints, and a diverse set of weapons designed with them in mind, so adding a hard counter would have destroyed much of what we had built. The result is that our new shields had to interact with all types of weapon.\n\n \n\nThe engine supports repulsion for non-plasma weapons, but the behaviour is inconsistent. Lasers bounce right off while rockets and missiles are turned away using their usual turn radius. Homing missiles even resume homing after they leave a shield, which looks a bit ridiculous and can make shields a liability. But the more general issue is that of cost: repulsion shields push projectiles away over time, which drains shield charge for as long as the projectile is within the shield. This is cool in that it lets an overwhelmed shield fail gradually, but it plays havoc with any attempt to balance drain rates. The speed of the projectile matters quite a bit, as does the angle at which it hits the shield, since glancing blows take less force to deflect. Particularly fast projectiles, such as riot cannons or tactical missiles, can penetrate quite deep into the shield before being significantly deflected. The charge drain of lasers was sensible, since they are reflected instantaneously, but attackers could still line up shots to drain charge from multiple shields at once.\n\nPerhaps these issues were solvable and, with enough tweaking, we could find a way to balance the cost of repelling all types of projectile. But the nail in the coffin for repulsion is that it offers units far too many ways to be stupid . It is undeniably cool to see shots flying around, but they mostly fly back at the army that shot them. One solution might be to have units aim slightly upwards, so the shots return over their heads, but this has two issues. Firstly, it is not a foolproof default, since the best way to drain a shield is often to shoot directly at it, so whether to risk friendly fire becomes an extra strategic decision. Secondly, we have gone to great lengths to avoid having units shoot into the sky , and allowing it opens up a whole new can of worms.\n\n

\n\nThe engine supports repulsion for non-plasma weapons, but the behaviour is inconsistent. Lasers bounce right off while rockets and missiles are turned away using their usual turn radius. Homing missiles even resume homing after they leave a shield, which looks a bit ridiculous and can make shields a liability. But the more general issue is that of cost: repulsion shields push projectiles away over time, which drains shield charge for as long as the projectile is within the shield. This is cool in that it lets an overwhelmed shield fail gradually, but it plays havoc with any attempt to balance drain rates. The speed of the projectile matters quite a bit, as does the angle at which it hits the shield, since glancing blows take less force to deflect. Particularly fast projectiles, such as riot cannons or tactical missiles, can penetrate quite deep into the shield before being significantly deflected. The charge drain of lasers was sensible, since they are reflected instantaneously, but attackers could still line up shots to drain charge from multiple shields at once.\n\nPerhaps these issues were solvable and, with enough tweaking, we could find a way to balance the cost of repelling all types of projectile. But the nail in the coffin for repulsion is that it offers units far too many ways to be stupid . It is undeniably cool to see shots flying around, but they mostly fly back at the army that shot them. One solution might be to have units aim slightly upwards, so the shots return over their heads, but this has two issues. Firstly, it is not a foolproof default, since the best way to drain a shield is often to shoot directly at it, so whether to risk friendly fire becomes an extra strategic decision. Secondly, we have gone to great lengths to avoid having units shoot into the sky , and allowing it opens up a whole new can of worms.\n\n \n\nIn the end, the fun physics had to be put aside, and shields became hard shells that block enemy projectiles. The projectiles are blocked by detonating them mid-air, and doing so costs shield charge equal to the damage of the projectile. If a shield has insufficient charge at the moment of impact, then the projectile is allowed through. Shields regenerate charge over time, and share charge around to try to equalise nearby shields. This is a fairly simple system, but there is enough to it to dial in some satisfying interactions.\n\nOne important technicality is that projectiles explode on shields, and this can even damage units behind the shield. It has to be this way since blocking the area-of-effect (AoE) damage of explosions damage would be a nightmare, both computationally and intuitively. A shield that blocked explosion damage would also have to block damage from shots that hit the ground just outside the shield, otherwise units would be incentivised to fire at the ground rather than into the shield, which would look silly. But damage should not be blocked for free, which implies that nearby explosions should consume shield charge. How much charge? Well, explosion damage is reduced by distance, but there is the potential for shields to be stacked behind each other, so shields would have to be able to protect each other. This is further complicated by the fact that units can straddle shield boundaries, making it unclear what is being protected. So rather than block area of effect damage, we embrace the fact that AoE is effective against shields, especially smaller personal shields.\n\n

\n\nIn the end, the fun physics had to be put aside, and shields became hard shells that block enemy projectiles. The projectiles are blocked by detonating them mid-air, and doing so costs shield charge equal to the damage of the projectile. If a shield has insufficient charge at the moment of impact, then the projectile is allowed through. Shields regenerate charge over time, and share charge around to try to equalise nearby shields. This is a fairly simple system, but there is enough to it to dial in some satisfying interactions.\n\nOne important technicality is that projectiles explode on shields, and this can even damage units behind the shield. It has to be this way since blocking the area-of-effect (AoE) damage of explosions damage would be a nightmare, both computationally and intuitively. A shield that blocked explosion damage would also have to block damage from shots that hit the ground just outside the shield, otherwise units would be incentivised to fire at the ground rather than into the shield, which would look silly. But damage should not be blocked for free, which implies that nearby explosions should consume shield charge. How much charge? Well, explosion damage is reduced by distance, but there is the potential for shields to be stacked behind each other, so shields would have to be able to protect each other. This is further complicated by the fact that units can straddle shield boundaries, making it unclear what is being protected. So rather than block area of effect damage, we embrace the fact that AoE is effective against shields, especially smaller personal shields.\n\n \n\nAnother notable part of the shield mechanics is that the interception threshold is per-projectile. So a shield at 599 charge lets through a 600 damage projectile, but would block half the damage of two shots that deal 300 damage each. Bursty units are balanced around this fact, with an extreme example being the 3000 damage Lance that deals damage in chunks of 150 over the course of a second. Phantom, with a single 1500-damage bullet, is generally better against shields for this reason. We have even used burst to buff units against shields, such as when the double-barrel shot of the Firewalker was split into ten projectiles, each with reduced AoE and more total direct damage. The interaction of burst damage and shields is one of the better kinds of emergent behaviour: one that players could reasonably puzzle out intuitively, rather than requiring the kind of deep dive that would be required to figure out how to optimally drain a repulsion shield. \n\nThe most unusual feature of Zero-K shields is something called shield link, which causes clusters of shields to gradually equalise their charge. It was most likely added to deal with the problem of wasted regeneration, since shields only regenerate when not fully charged. Minimising mid-combat regeneration is important when fighting shields, which can be achieved via focus fire. However, mobile shield generators can negate focus fire by dancing around so that each shield gets a turn at the front. This is a case of skipping the unit AI arms race by implementing the final result, so charge from high-charge shields flows to nearby shields of lower charge, leaving more space for regeneration.\n\nShield link turned out to be a buff to burst damage because it caused clumps of shields to lose charge together, rather than individually. The best demonstration of this is the way tacnukes counter shields. A tacnuke deals 3500 damage, while large shields have 3600 charge, so without shield link you would need to spend one tacnuke per shield to drain a cluster enough to start penetrating it. With shield link, a single tacnuke can disable any reasonably sized cluster. All you need to do is fire the first tacnuke, wait a few seconds, then fire the followup. Charge rushes into the newly depleted shield after the first tacnuke hits, so by the time the second volley arrives there are no shields capable of stopping a tacnuke.\n\n

\n\nAnother notable part of the shield mechanics is that the interception threshold is per-projectile. So a shield at 599 charge lets through a 600 damage projectile, but would block half the damage of two shots that deal 300 damage each. Bursty units are balanced around this fact, with an extreme example being the 3000 damage Lance that deals damage in chunks of 150 over the course of a second. Phantom, with a single 1500-damage bullet, is generally better against shields for this reason. We have even used burst to buff units against shields, such as when the double-barrel shot of the Firewalker was split into ten projectiles, each with reduced AoE and more total direct damage. The interaction of burst damage and shields is one of the better kinds of emergent behaviour: one that players could reasonably puzzle out intuitively, rather than requiring the kind of deep dive that would be required to figure out how to optimally drain a repulsion shield. \n\nThe most unusual feature of Zero-K shields is something called shield link, which causes clusters of shields to gradually equalise their charge. It was most likely added to deal with the problem of wasted regeneration, since shields only regenerate when not fully charged. Minimising mid-combat regeneration is important when fighting shields, which can be achieved via focus fire. However, mobile shield generators can negate focus fire by dancing around so that each shield gets a turn at the front. This is a case of skipping the unit AI arms race by implementing the final result, so charge from high-charge shields flows to nearby shields of lower charge, leaving more space for regeneration.\n\nShield link turned out to be a buff to burst damage because it caused clumps of shields to lose charge together, rather than individually. The best demonstration of this is the way tacnukes counter shields. A tacnuke deals 3500 damage, while large shields have 3600 charge, so without shield link you would need to spend one tacnuke per shield to drain a cluster enough to start penetrating it. With shield link, a single tacnuke can disable any reasonably sized cluster. All you need to do is fire the first tacnuke, wait a few seconds, then fire the followup. Charge rushes into the newly depleted shield after the first tacnuke hits, so by the time the second volley arrives there are no shields capable of stopping a tacnuke.\n\n \n\nShields would rather not be exploitable by tacnukes, but as we saw 25 posts ago , shield link is not optional. The downside of shield link gives shields space to be powerful in small numbers without becoming that much more powerful when spammed. This is the sweet spot we aim for across Zero-K as it encourages people to use a mix of tools , and it is especially important for mechanics that can slow down the game by preventing damage. The goal is to see a bit of shielding in many battles, rather than a lot in a few. This goes all the way back to the decision to make mobile shields and cloakers available to all factories by being available as a morph from their static versions .\n\nOn the technical side, shield link has been through two iterations. It was originally a deterministic algorithm that would have each shield poll its neighbours and move closer to the average, adjusting each neighbour by the same amount. This had performance issues and edge cases, so was replaced by a random sampling approach. Now shield link works by having each shield select a random neighbour to exchange charge with, 15 times a second. This is fast enough for random variations to average out, and it is much simpler than the previous approach.\n\n

\n\nShields would rather not be exploitable by tacnukes, but as we saw 25 posts ago , shield link is not optional. The downside of shield link gives shields space to be powerful in small numbers without becoming that much more powerful when spammed. This is the sweet spot we aim for across Zero-K as it encourages people to use a mix of tools , and it is especially important for mechanics that can slow down the game by preventing damage. The goal is to see a bit of shielding in many battles, rather than a lot in a few. This goes all the way back to the decision to make mobile shields and cloakers available to all factories by being available as a morph from their static versions .\n\nOn the technical side, shield link has been through two iterations. It was originally a deterministic algorithm that would have each shield poll its neighbours and move closer to the average, adjusting each neighbour by the same amount. This had performance issues and edge cases, so was replaced by a random sampling approach. Now shield link works by having each shield select a random neighbour to exchange charge with, 15 times a second. This is fast enough for random variations to average out, and it is much simpler than the previous approach.\n\n \n\nThe last issue for today concerns status effects. Weapons should generally interact with shields, and thematically it would be weird for a lightning bolt to ignore shields or to be harmlessly dissipated. But letting shields take EMP, disarm or slow damage as if they were fully independent units would be too complicated. So to keep things simple, status effects deal damage to shield charge, just like ordinary damage, with caveats. The damage numbers of status effects are quite a bit higher than those of ordinary damage, since status effect damage has to hit health thresholds to take effect. Their raw damage would completely annihilate shields, so status effects only deal a third of their damage to shields. This is one of the rare instances of damage multipliers in Zero-K, and it is still enough damage to make lightning and slow damage some of the most effective ways to drain a shield.\n\nShields eventually ended up in a good spot, after being nerfed over the years, and are now a powerful-but-optional tool. They play a lesser role in cross-map artillery battles than they used to, but this is mostly due to terraform offering alternate ways to hunker down and the advent of the shield-overwhelming Odin bomber . Shields are stable, although throughout this post I have tried, and failed, to convince myself to revisit repulsion shields. Perhaps that is what modding is for, and there is surely an entirely new game to be made about bouncing projectiles around. As a final note, the Funnelweb shield does not behave like other shields, but details will have to wait for another post.\n\nThis is the last Cold Take of 2025. We are taking a break over December and expect to return in January. \n\nIndex of Cold Takes \n\n

\n\nThe last issue for today concerns status effects. Weapons should generally interact with shields, and thematically it would be weird for a lightning bolt to ignore shields or to be harmlessly dissipated. But letting shields take EMP, disarm or slow damage as if they were fully independent units would be too complicated. So to keep things simple, status effects deal damage to shield charge, just like ordinary damage, with caveats. The damage numbers of status effects are quite a bit higher than those of ordinary damage, since status effect damage has to hit health thresholds to take effect. Their raw damage would completely annihilate shields, so status effects only deal a third of their damage to shields. This is one of the rare instances of damage multipliers in Zero-K, and it is still enough damage to make lightning and slow damage some of the most effective ways to drain a shield.\n\nShields eventually ended up in a good spot, after being nerfed over the years, and are now a powerful-but-optional tool. They play a lesser role in cross-map artillery battles than they used to, but this is mostly due to terraform offering alternate ways to hunker down and the advent of the shield-overwhelming Odin bomber . Shields are stable, although throughout this post I have tried, and failed, to convince myself to revisit repulsion shields. Perhaps that is what modding is for, and there is surely an entirely new game to be made about bouncing projectiles around. As a final note, the Funnelweb shield does not behave like other shields, but details will have to wait for another post.\n\nThis is the last Cold Take of 2025. We are taking a break over December and expect to return in January. \n\nIndex of Cold Takes \n\n

This is a guest post by Aquanim, who led the 2016 sea rework.\n\nOver two thirds of our own planet is covered by oceans. Therefore, strategy games which are played on planetary landscapes have some reason to consider how to handle bodies of water. The simplest approach is to treat water bodies as an impassable barrier to land units and leave it at that. In games where units can interact with water, often this is reserved for a special class of ship-type units, but beyond this distinction water is just another terrain type.\n\nThe physics-driven mechanics of Zero-K require us to give some deeper thought to how units ought to behave on and around water. This goes all the way down to fundamentals like where is the water, where can units go, when can units see each other, and how do units fight each other. We can dispose of the first point quickly: the sea level is defined by the engine to be altitude zero, so unfortunately we cant have fancy waterfalls or scenic mountain lakes.\n\n \n\nOn land, all units (which are not flying, jumping or thrown) are standing on the ground. That ground might be flat, precipitous or anything in between. In water, on the other hand, there are four places a unit might plausibly be:

\n\nOn land, all units (which are not flying, jumping or thrown) are standing on the ground. That ground might be flat, precipitous or anything in between. In water, on the other hand, there are four places a unit might plausibly be:

- \n

- Hovering above the water surface\n

- On the water surface\n

- Floating beneath the surface\n

- On the seafloor\n

\n\nVerisimilitude demands that units under the water are more difficult to see than those on the surface. However, just like the ordinary fog-of-war mechanics deviate from `realistic line-of-sight for the purposes of gameplay, we simplify seeing underwater to a single mechanic, sonar. An enemy underwater unit is visible to us if and only if it is within the sonar radius of a friendly unit. To make things even simpler, in modern Zero-K all sea units have sonar radius equal to their vision radius, while most other units do not (notably the Owl scout plane has limited sonar capability). \n\nUnderwater units are still stealthier than surface units, since they dont show up on long-range radar and cannot be detected by non-combat buildings like metal extractors. They are not as hidden as cloaked units, which seems reasonable since cloaked units are less common and normally pay a cost in terms of energy or immobility. As previously mentioned, units underwater cannot be cloaked, since the decloak radius mechanic would not play nicely with variable water depths.\n\nBesides the gameplay mechanics associated with vision, sea maps also pose a visual clarity problem to the player. Between the tint of the sea, surface ripples and reflections, units operating at several different depths, and typically less informative terrain textures, it is often more difficult to tell exactly what is going on underwater. This is part of the reason why underwater combat in Zero-K has few weapon types, and those that exist do not strongly reward quick reactions and micromanagement.\n\n

\n\nVerisimilitude demands that units under the water are more difficult to see than those on the surface. However, just like the ordinary fog-of-war mechanics deviate from `realistic line-of-sight for the purposes of gameplay, we simplify seeing underwater to a single mechanic, sonar. An enemy underwater unit is visible to us if and only if it is within the sonar radius of a friendly unit. To make things even simpler, in modern Zero-K all sea units have sonar radius equal to their vision radius, while most other units do not (notably the Owl scout plane has limited sonar capability). \n\nUnderwater units are still stealthier than surface units, since they dont show up on long-range radar and cannot be detected by non-combat buildings like metal extractors. They are not as hidden as cloaked units, which seems reasonable since cloaked units are less common and normally pay a cost in terms of energy or immobility. As previously mentioned, units underwater cannot be cloaked, since the decloak radius mechanic would not play nicely with variable water depths.\n\nBesides the gameplay mechanics associated with vision, sea maps also pose a visual clarity problem to the player. Between the tint of the sea, surface ripples and reflections, units operating at several different depths, and typically less informative terrain textures, it is often more difficult to tell exactly what is going on underwater. This is part of the reason why underwater combat in Zero-K has few weapon types, and those that exist do not strongly reward quick reactions and micromanagement.\n\n \n\nA second constraint on the weapons which are usable by and against underwater units is that the game mechanics must remain reasonable for a fairly wide range of water depths. Imagine, for example, a surface unit with an unguided torpedo with similar mechanics to the Ronins missile, firing at a group of Ducks on the sea floor. In shallow water the path of the torpedo traces a straight line lengthways through the Ducks, and is likely to hit one. In deep water the torpedo will instead have only a brief window where it is at an appropriate depth to hit the Ducks before it impacts the ground. This all sounds rather messy, so we have given all underwater-capable weapons tracking or other projectile properties which avoid this discrepancy.\n\nFrom the perspective of balance rather than design, there is yet another constraint on underwater-capable weapons: if the longest-range conventional underwater-targeting weapon is itself attached to an underwater unit, then there is a lot of danger that these units will become dominant in the sea meta, since if they can be protected against swarms there is little else which can outscale them. Addressing this by expanding the surface-vs-underwater game with a wide range of units and capabilities is a superficially interesting idea, but has two big drawbacks. First, as we have already discussed, the potential variety in sensible underwater-capable weapons is rather limited. Second, while surface units can directly interact with land units and vice versa in interesting ways, it seems much more difficult to have land units and underwater units interact well. \n\nTherefore, in Zero-K we have gone in the direction of reducing underwater interactions to the minimum feasible set - of the units below strider class, only the light submarine and a few Amphbots can fight underwater, and all of their weapons have short ranges. The old Serpent long-range sniper submarine is one of the very few units to have been outright removed from Zero-K in the last decade (well get to the second one later), and Scallops skirmisher-range torpedoes were reduced to riot range (though this was by no means the end of Scallops career as a game-warping balance headache)\n\nSince very few land-based assets can interact with submerged units, it would be quite unfair for underwater units to engage land units freely without fear of retaliation. Therefore, the only unit with a weapon designed for underwater-to-land combat is the Scylla tactical missile submarine, which pays a metal cost for each missile and hence does not engage freely.\n\n

\n\nA second constraint on the weapons which are usable by and against underwater units is that the game mechanics must remain reasonable for a fairly wide range of water depths. Imagine, for example, a surface unit with an unguided torpedo with similar mechanics to the Ronins missile, firing at a group of Ducks on the sea floor. In shallow water the path of the torpedo traces a straight line lengthways through the Ducks, and is likely to hit one. In deep water the torpedo will instead have only a brief window where it is at an appropriate depth to hit the Ducks before it impacts the ground. This all sounds rather messy, so we have given all underwater-capable weapons tracking or other projectile properties which avoid this discrepancy.\n\nFrom the perspective of balance rather than design, there is yet another constraint on underwater-capable weapons: if the longest-range conventional underwater-targeting weapon is itself attached to an underwater unit, then there is a lot of danger that these units will become dominant in the sea meta, since if they can be protected against swarms there is little else which can outscale them. Addressing this by expanding the surface-vs-underwater game with a wide range of units and capabilities is a superficially interesting idea, but has two big drawbacks. First, as we have already discussed, the potential variety in sensible underwater-capable weapons is rather limited. Second, while surface units can directly interact with land units and vice versa in interesting ways, it seems much more difficult to have land units and underwater units interact well. \n\nTherefore, in Zero-K we have gone in the direction of reducing underwater interactions to the minimum feasible set - of the units below strider class, only the light submarine and a few Amphbots can fight underwater, and all of their weapons have short ranges. The old Serpent long-range sniper submarine is one of the very few units to have been outright removed from Zero-K in the last decade (well get to the second one later), and Scallops skirmisher-range torpedoes were reduced to riot range (though this was by no means the end of Scallops career as a game-warping balance headache)\n\nSince very few land-based assets can interact with submerged units, it would be quite unfair for underwater units to engage land units freely without fear of retaliation. Therefore, the only unit with a weapon designed for underwater-to-land combat is the Scylla tactical missile submarine, which pays a metal cost for each missile and hence does not engage freely.\n\n \n\nWe conclude with a lightning round covering other interesting aspects of Zero-Ks sea design.\n\nEconomy: The core principles of Zero-Ks economy remain the same on water maps, but there are some differences which alter the typical play patterns (adding some desirable variety). Arguably the most important is an indirect consequence of where units can move. The wrecks of destroyed units fall to the seafloor, where they are much less prone to being trampled or reduced by stray weapon fire. Therefore, metal reclaim is often a major factor in prolonged sea battles. Since wind generators perform poorly at sea level they are replaced with tidal generators, which combine the efficiency of wind generators with the reliability and robustness of solar collectors. Singularity Reactors cannot be built underwater, though one can terraform a land platform on which to place them. This is motivated by similar reasons as the decision to prevent cloaking of structures in general, and gives Fusion Reactors a point of difference.\n\nFactory balance: Across the land-based factories there is a (tenuous) principle that each factory should be similarly powerful and competitive with each other in a 1v1 on a suitable map. We dont hold to the same rule in sea battles for two reasons. First, it would be boring to do the same thing twice. Second, since they are unable to travel on land, Ships have less freedom of movement than the hybrid Hover and Amph factories, which makes a difference even on maps which only have small islands. Therefore, our (tenuous) goal is for the Ship units to be a bit overtuned, but the Hover, Amphbot and air factories should still provide useful tools.\n\nLandships: Okay, I lied. Ships can go on land sort of. Lobsters, air transports, or terraforming can put a ship on land, and while the ship cant move around without assistance it can still fight. The Envoy and Shogun artillery ships make the best use of this, since their long range mitigates mobility problems and their ballistic weapons benefit from higher elevation.\n\nTransports: Unlike almost every other game with a dedicated class of ship units, Zero-K does not have a conventional transport for land units across bodies of water. The Surfboard used to fill this role, but it did not have much purpose when compared with the Djinn teleporter and Charon air transport, and was eventually consigned to the ship graveyard alongside the Serpent.\n\nSpicy water: Some maps replace water with acid, lava, or void. On these maps Zero-K behaves much more like the water is an impassable barrier games we mentioned at the start, although some acid is weak enough that units can survive in it for a while. These maps are not affected by most of the issues described in this post, but they do offer some novel tactical opportunities of their own\n\nCome back in a few weeks for Cold Take #35, in which we will stop building a navy.\n\nIndex of Cold Takes \n

\n\nWe conclude with a lightning round covering other interesting aspects of Zero-Ks sea design.\n\nEconomy: The core principles of Zero-Ks economy remain the same on water maps, but there are some differences which alter the typical play patterns (adding some desirable variety). Arguably the most important is an indirect consequence of where units can move. The wrecks of destroyed units fall to the seafloor, where they are much less prone to being trampled or reduced by stray weapon fire. Therefore, metal reclaim is often a major factor in prolonged sea battles. Since wind generators perform poorly at sea level they are replaced with tidal generators, which combine the efficiency of wind generators with the reliability and robustness of solar collectors. Singularity Reactors cannot be built underwater, though one can terraform a land platform on which to place them. This is motivated by similar reasons as the decision to prevent cloaking of structures in general, and gives Fusion Reactors a point of difference.\n\nFactory balance: Across the land-based factories there is a (tenuous) principle that each factory should be similarly powerful and competitive with each other in a 1v1 on a suitable map. We dont hold to the same rule in sea battles for two reasons. First, it would be boring to do the same thing twice. Second, since they are unable to travel on land, Ships have less freedom of movement than the hybrid Hover and Amph factories, which makes a difference even on maps which only have small islands. Therefore, our (tenuous) goal is for the Ship units to be a bit overtuned, but the Hover, Amphbot and air factories should still provide useful tools.\n\nLandships: Okay, I lied. Ships can go on land sort of. Lobsters, air transports, or terraforming can put a ship on land, and while the ship cant move around without assistance it can still fight. The Envoy and Shogun artillery ships make the best use of this, since their long range mitigates mobility problems and their ballistic weapons benefit from higher elevation.\n\nTransports: Unlike almost every other game with a dedicated class of ship units, Zero-K does not have a conventional transport for land units across bodies of water. The Surfboard used to fill this role, but it did not have much purpose when compared with the Djinn teleporter and Charon air transport, and was eventually consigned to the ship graveyard alongside the Serpent.\n\nSpicy water: Some maps replace water with acid, lava, or void. On these maps Zero-K behaves much more like the water is an impassable barrier games we mentioned at the start, although some acid is weak enough that units can survive in it for a while. These maps are not affected by most of the issues described in this post, but they do offer some novel tactical opportunities of their own\n\nCome back in a few weeks for Cold Take #35, in which we will stop building a navy.\n\nIndex of Cold Takes \nSlow damage is the more prolific, yet less dramatic, cousin of EMP and disarm . It is weaker than EMP in that it never fully disables a unit, but the effect gradually ramps up from the very first instance of damage, making it useful in more situations. This gradual but persistent effect let us spread slow across more weapon types and roles, to the point it became a meme. But whereas EMP was inherited from pre-Complete Annihilation modding, slow was created from scratch, and upon reviewing the history it is somewhat surprising that it came to exist at all.\n\nLast time we covered the development of EMP, and how it became synonymous with lightning. But I did not mention that both stun and lightning were exclusive to Arm in Total Annihilation, and this focus was mostly carried through by TA modders. Complete Annihilation pushed faction differentiation hard, so when we merged lightning with stun, the smattering of Core stuns were moved to Arm. This gave Arm a monopoly on disabling status effects, which proved to be a bit too one-sided. Even though Core had a few more damaging options, such as a tacnuke missile to mirror the Arm tactical EMP missile, we eventually looked for a way to break the monopoly.\n\n \n\nSlow damage was the solution to the Arm monopoly on status effects: a new status effect just for Core. I recall MidKnight adding it as an alternative to moving the main Core stun unit, the Gnat-equivalent, to Arm. Gnat ultimately gained lightning and was transferred, but slow stuck around. Numerous Core units gained slow damage over the years, until the mechanic found its home as a core aspect of the Amphbot factory. This factory was added after we merged the factions , yet in many ways maintains the old Core aesthetic of raw power and toughness.\n\nThe underlying mechanics of slow damage have been quite stable over the last 16 years. Slow damage accumulates on units and is shown on a bar under their main health bar, the same as EMP. Units with slow damage are slowed immediately by an amount equal to the accumulated slow damage as a fraction of current health. For example, a unit with 1000 health and 150 slow damage is slowed by 15%. Slow damage is capped at 50% of current health (with a few exceptions) and decays over time at a rate of 4% per second, although decay is halted for half a second after taking slow damage.\n\nSome slow weapons (Moderator, Limpet, and Disco Rave Party) can push units to 58% slow damage, but still only slow them by 50%. Slow decays at 4% per second, so this corresponds to two extra seconds at full slow. But this is not the only way to extend a lingering slow, since regular damage reduces health, which increases slow as a fraction of current health. This interaction between status effect percentage and current health was a huge problem for EMP, but slow decays so quickly that it rarely matters.\n\n

\n\nSlow damage was the solution to the Arm monopoly on status effects: a new status effect just for Core. I recall MidKnight adding it as an alternative to moving the main Core stun unit, the Gnat-equivalent, to Arm. Gnat ultimately gained lightning and was transferred, but slow stuck around. Numerous Core units gained slow damage over the years, until the mechanic found its home as a core aspect of the Amphbot factory. This factory was added after we merged the factions , yet in many ways maintains the old Core aesthetic of raw power and toughness.\n\nThe underlying mechanics of slow damage have been quite stable over the last 16 years. Slow damage accumulates on units and is shown on a bar under their main health bar, the same as EMP. Units with slow damage are slowed immediately by an amount equal to the accumulated slow damage as a fraction of current health. For example, a unit with 1000 health and 150 slow damage is slowed by 15%. Slow damage is capped at 50% of current health (with a few exceptions) and decays over time at a rate of 4% per second, although decay is halted for half a second after taking slow damage.\n\nSome slow weapons (Moderator, Limpet, and Disco Rave Party) can push units to 58% slow damage, but still only slow them by 50%. Slow decays at 4% per second, so this corresponds to two extra seconds at full slow. But this is not the only way to extend a lingering slow, since regular damage reduces health, which increases slow as a fraction of current health. This interaction between status effect percentage and current health was a huge problem for EMP, but slow decays so quickly that it rarely matters.\n\n \n\nSlow has driven and benefited from the development of increasingly powerful gadgetry . There is no stated limit on what can be slowed, so we have gradually expanded its scope by making more and more things slowable. Almost everything is covered at this point, including movement speeds, reload times, and economic rates, with the main exception being jump speed. This is great for modding, and shows off the power of the engine, since slow would be harder to implement in an engine that updated less than 30 times a second. The high tick rate lets us treat time as continuous without too many issues, even though actions only happen every 33 milliseconds.\n\nThere are some caveats to be aware of when slowing rapid-fire weapons. For example, the Light Laser Tower seems to shoot a continuous laser, but it actually fires a 0.1 second burst every 0.1 seconds. This corresponds to one shot per 3 frames, which increases to one shot per 6 frames when slowed by 50%, as expected. However, when slowed by 45%, it shoots once every 4 frames, for 40% reduction in damage output instead of 45%. This barely matters for how Zero-K uses slow, but would matter for a mod that, say, implements global fire rate upgrades and expects the increase in damage output to be absolutely consistent across units.\n\n

\n\nSlow has driven and benefited from the development of increasingly powerful gadgetry . There is no stated limit on what can be slowed, so we have gradually expanded its scope by making more and more things slowable. Almost everything is covered at this point, including movement speeds, reload times, and economic rates, with the main exception being jump speed. This is great for modding, and shows off the power of the engine, since slow would be harder to implement in an engine that updated less than 30 times a second. The high tick rate lets us treat time as continuous without too many issues, even though actions only happen every 33 milliseconds.\n\nThere are some caveats to be aware of when slowing rapid-fire weapons. For example, the Light Laser Tower seems to shoot a continuous laser, but it actually fires a 0.1 second burst every 0.1 seconds. This corresponds to one shot per 3 frames, which increases to one shot per 6 frames when slowed by 50%, as expected. However, when slowed by 45%, it shoots once every 4 frames, for 40% reduction in damage output instead of 45%. This barely matters for how Zero-K uses slow, but would matter for a mod that, say, implements global fire rate upgrades and expects the increase in damage output to be absolutely consistent across units.\n\n \n\nThe first recipients of slow damage were Outlaw and Moderator. The Outlaw used to be a standard riot armed with a Bandit blaster in one hand and a Ripper gun (then Leveler) in the other, which is where we get the phrase \"Leveler sidearm\". It gained the disruptor pulse while the rest of Core T1 bots were undergoing a shield makeover, since friendly-fire-less area of effect damage works great in a shield ball. The disruptor pulse is unique in that it does not damage allied units, and was conceptualised as some sort of control system attack.\n\nModerator gained slow because the old Moderator was too generic . This left it prone to being monospammed, and it was hemmed in by similar units on all sides. Imagine a long-range skirmisher like Rogue, with a Sling-like plasma cannon, and the weight of a Recluse. Range is particularly hard to balance in RTS, especially for units that can fire while moving, so in Zero-K it comes with severe drawbacks; Recluse and Sling are flimsy, Bulkhead and Fencer deploy to fire, and Rogue has a very slow projectile. The design space around Moderator was too full or troublesome to find it a healthy place, so we gave it slow.\n\n

\n\nThe first recipients of slow damage were Outlaw and Moderator. The Outlaw used to be a standard riot armed with a Bandit blaster in one hand and a Ripper gun (then Leveler) in the other, which is where we get the phrase \"Leveler sidearm\". It gained the disruptor pulse while the rest of Core T1 bots were undergoing a shield makeover, since friendly-fire-less area of effect damage works great in a shield ball. The disruptor pulse is unique in that it does not damage allied units, and was conceptualised as some sort of control system attack.\n\nModerator gained slow because the old Moderator was too generic . This left it prone to being monospammed, and it was hemmed in by similar units on all sides. Imagine a long-range skirmisher like Rogue, with a Sling-like plasma cannon, and the weight of a Recluse. Range is particularly hard to balance in RTS, especially for units that can fire while moving, so in Zero-K it comes with severe drawbacks; Recluse and Sling are flimsy, Bulkhead and Fencer deploy to fire, and Rogue has a very slow projectile. The design space around Moderator was too full or troublesome to find it a healthy place, so we gave it slow.\n\n \n\nA few units gained slow for similar reasons to Moderator, to the point that \"give it slow\" became a meme. This was done to units that were underwhelming or lacking a distinct role. The skirmisher gunship Harpy was in an awkward spot between the faster Locust and tougher Revenant, while Dart lacked a clear purpose within Rover. Cyclops used to have a flamethrower sidearm, but this made it hard to counter with swarms, so it was switched out for a slow beam to give it utility over Minotaur. Seawolf gained a slowing torpedo as part of a sea rework.\n\nSlow damage was also a popular choice for brand new units. The Amphbot factory was created after factories replaced factions, so it could have contained anything, but we decided to make slow one of its main mechanics. To some extent, Buoy deals slow damage because little room remained for an ordinary skirmisher of its class, and Limpet explodes with slow damage because the other bomb types were taken . But we had better reasons to give the factory slow. Part of the plan was to make a particularly slow moving factory which could use slow damage to bring the enemy down to its own speed. The idea behind the large disruptor pulse of the Limpet was to let it reach the surface of the water from the ocean floor.\n\nThe strongest reason for Buoy to deal slow damage is that slow is good against heavy units, and ships tend to be heavy. Heavy units are weak to slow because they tend to live longer, which gives the effect more time to have an impact. Slow also makes it harder to retreat for repairs, which is a big part of using heavy units. Bolas, the disruptor beam hovercraft raider, was added to Hovercraft for a similar reason, although admittedly it also deals slow because no other proper raider does so.\n\n

\n\nA few units gained slow for similar reasons to Moderator, to the point that \"give it slow\" became a meme. This was done to units that were underwhelming or lacking a distinct role. The skirmisher gunship Harpy was in an awkward spot between the faster Locust and tougher Revenant, while Dart lacked a clear purpose within Rover. Cyclops used to have a flamethrower sidearm, but this made it hard to counter with swarms, so it was switched out for a slow beam to give it utility over Minotaur. Seawolf gained a slowing torpedo as part of a sea rework.\n\nSlow damage was also a popular choice for brand new units. The Amphbot factory was created after factories replaced factions, so it could have contained anything, but we decided to make slow one of its main mechanics. To some extent, Buoy deals slow damage because little room remained for an ordinary skirmisher of its class, and Limpet explodes with slow damage because the other bomb types were taken . But we had better reasons to give the factory slow. Part of the plan was to make a particularly slow moving factory which could use slow damage to bring the enemy down to its own speed. The idea behind the large disruptor pulse of the Limpet was to let it reach the surface of the water from the ocean floor.\n\nThe strongest reason for Buoy to deal slow damage is that slow is good against heavy units, and ships tend to be heavy. Heavy units are weak to slow because they tend to live longer, which gives the effect more time to have an impact. Slow also makes it harder to retreat for repairs, which is a big part of using heavy units. Bolas, the disruptor beam hovercraft raider, was added to Hovercraft for a similar reason, although admittedly it also deals slow because no other proper raider does so.\n\n \n\nWe avoided adding too much slow, but it has still accumulated over the years without really considering what it is in the game world. Is it time dilation, or perhaps a virus, as implied by Outlaw? Are units being mechanically gummed up by some sort of purple goo? Slow damage is dealt by various types of missile, beam and arcing projectile, with the only unifying characteristic being the colour purple. Compared to the consistency of lightning and EMP it is a bit of a mess. This may be a minor problem, but systems generally feel better when presented in a consistent way.\n\nOf the twelve sources of slow damage, only one, the tactical missile, deals pure slow. This is not for want of trying, since the original slow Moderator was a slow-only unit. However, we failed to find a place for it where it was not either too niche, or too obnoxious. Part of this issue is that status effect-only weapons risk cluttering the screen and soundscape without progressing the game. Racketeer, the disarming artillery, suffers from this exact issue, but the greater utility of disarm over slow lets it feel powerful without spamming projectiles. Pure status effects also give units more ways to be stupid , since spreading the effect around becomes more central to the usefulness of the unit.\n\n

\n\nWe avoided adding too much slow, but it has still accumulated over the years without really considering what it is in the game world. Is it time dilation, or perhaps a virus, as implied by Outlaw? Are units being mechanically gummed up by some sort of purple goo? Slow damage is dealt by various types of missile, beam and arcing projectile, with the only unifying characteristic being the colour purple. Compared to the consistency of lightning and EMP it is a bit of a mess. This may be a minor problem, but systems generally feel better when presented in a consistent way.\n\nOf the twelve sources of slow damage, only one, the tactical missile, deals pure slow. This is not for want of trying, since the original slow Moderator was a slow-only unit. However, we failed to find a place for it where it was not either too niche, or too obnoxious. Part of this issue is that status effect-only weapons risk cluttering the screen and soundscape without progressing the game. Racketeer, the disarming artillery, suffers from this exact issue, but the greater utility of disarm over slow lets it feel powerful without spamming projectiles. Pure status effects also give units more ways to be stupid , since spreading the effect around becomes more central to the usefulness of the unit.\n\n \n\nThese days most slow damage weapons deal slow as a bonus, rather than as their primary purpose. Outlaw, Moderator, Buoy and Constable would be much worse without slow, but with a corresponding cost decrease, would probably still find use. It would be interesting to experiment with more pure slow, but for now, slow provides a much-needed counters for heavy units and mitigates a bit of damage. The more dedicated sources of slow, such as those with large area of effect, are fairly niche, but this is probably preferable to permanently playing the game at half speed.\n\nIndex of Cold Takes

\n\nThese days most slow damage weapons deal slow as a bonus, rather than as their primary purpose. Outlaw, Moderator, Buoy and Constable would be much worse without slow, but with a corresponding cost decrease, would probably still find use. It would be interesting to experiment with more pure slow, but for now, slow provides a much-needed counters for heavy units and mitigates a bit of damage. The more dedicated sources of slow, such as those with large area of effect, are fairly niche, but this is probably preferable to permanently playing the game at half speed.\n\nIndex of Cold Takes

This update has tweaks and fixes for the update from two weeks ago. Detriment now responds to status effects while winding up its jump, and being transported cancels the jump entirely. Racketeer is also better at keeping large units disabled.\n\n

Tweaks

\n\nStatus effects and transportation interact with the jump windup of Jugglenaut and Detriment.- \n

- Stun and disarm pause windup progress. Jump cannot be cancelled or re-targeted this way.\n

- Slow makes the windup take longer.\n

- Picking up a winding up unit in a transport cancels the jump and wastes the reload.\n

Fixes

\n- \n

- Opening the menu no longer pauses games that started with more than one player.\n

- Fixed Cerberus not firing when built at exactly the wrong elevation.\n

- Fixed planet Harsar Lief (Shipyard unlock).\n

- Fixed metal extractor tooltip bug on metal maps.\n

- Fixed reset hotkeys button bug on pages with multiple default hotkeys.\n

- Fixed build ETA and overhead icon height to match healthbar offset height.\n

- Fixed missing stockpile command texture in the command menu.\n

Strategy games present players with an evolving set of problems and a selection of tools with which to solve them. The problems in RTS tend to boil down to the fact that the enemy has units, so a lot of the tools offer ways to damage and destroy units. But using the same type of tool over and over can feel repetitive, so many games also give players ways to weaken enemy units without killing them. These non-lethal tools are known as status effects, or debuffs, and they add variety by letting players weave non-destructive actions into their battle plans.\n\nSome games do without status effects, but the goals of Zero-K demand a large toolbox, so ignoring status effects was not an option. The first status effect, known as either paralysis or stun, was present in our earlier ancestor, Total Annihilation , although it made little use of it. In fact TA had two sources of stun: the Spider and a global-range EMP missile. The Spider could disable a single target by continually firing at it, while the EMP missile disabled Core units in an area. This faction specificity was due to Core being a faction of robots, while Arm units are piloted, which made them immune to EMP. Core struck back though with the Arm-killing Neutron missile.\n\n \n\nModders went to town on TA and added a few more stun units - but haphazardly. I suspect paralysis was a niche mechanic since TA barely told players how the mechanic worked, it did not even indicate whether a unit was stunned or not. Spring (the engine behind Zero-K) did a lot better in this regard, but there was still not much more by the time Complete Annihilation entered the scene. Arm had gained a few EMP death explosions and some stun sidearms, while Core had a Gnat-like cheap stun drone. The faction-specific effect of the EMP and Neutron missiles were also removed at some point. From here we expanded the arsenal and fixed issues with the underlying systems.\n\nOne of the early goals of Complete Annihilation was to overhaul the weapon visuals, and part of this involved consistency between the visuals and the underlying mechanics. This means that dissimilar weapons should look different, and also that similar weapons should avoid implying a mechanical difference by arbitrarily varying their visuals. This was bad news for the plain-looking paralysis lasers, but the new idea also highlighted the fancy lightning weapons as a problem, since they were little more than pulse lasers mechanically. These problems solved each other when we gave all lightning weapons the ability to stun and reskinned the existing stun effects to shoot lightning.\n\nGiving EMP damage a unique weapon type was a start, but we also had to balance EMP around the removal of armour classes . Several units were resistant or immune to EMP damage, including commanders, units that deal EMP damage, and striders. Strider EMP immunity was perhaps the most egregious, since disabling a single huge unit is a great application of EMP. Players should be rewarded for playing around their tools to come up with something powerful, not butt up against arbitrary constraints. Most things can be balanced around, so removing something for being \"too OP\" is a last resort, as hidden restrictions punish unaware players and make them distrust the tools the game gave them in the process.\n\n

\n\nModders went to town on TA and added a few more stun units - but haphazardly. I suspect paralysis was a niche mechanic since TA barely told players how the mechanic worked, it did not even indicate whether a unit was stunned or not. Spring (the engine behind Zero-K) did a lot better in this regard, but there was still not much more by the time Complete Annihilation entered the scene. Arm had gained a few EMP death explosions and some stun sidearms, while Core had a Gnat-like cheap stun drone. The faction-specific effect of the EMP and Neutron missiles were also removed at some point. From here we expanded the arsenal and fixed issues with the underlying systems.\n\nOne of the early goals of Complete Annihilation was to overhaul the weapon visuals, and part of this involved consistency between the visuals and the underlying mechanics. This means that dissimilar weapons should look different, and also that similar weapons should avoid implying a mechanical difference by arbitrarily varying their visuals. This was bad news for the plain-looking paralysis lasers, but the new idea also highlighted the fancy lightning weapons as a problem, since they were little more than pulse lasers mechanically. These problems solved each other when we gave all lightning weapons the ability to stun and reskinned the existing stun effects to shoot lightning.\n\nGiving EMP damage a unique weapon type was a start, but we also had to balance EMP around the removal of armour classes . Several units were resistant or immune to EMP damage, including commanders, units that deal EMP damage, and striders. Strider EMP immunity was perhaps the most egregious, since disabling a single huge unit is a great application of EMP. Players should be rewarded for playing around their tools to come up with something powerful, not butt up against arbitrary constraints. Most things can be balanced around, so removing something for being \"too OP\" is a last resort, as hidden restrictions punish unaware players and make them distrust the tools the game gave them in the process.\n\n \n\nLightning weapons stun units by dealing EMP damage that accumulates on their target. This alternate damage type sits alongside health and is displayed under the main health bar. A unit becomes stunned when the EMP damage it has taken exceeds its current health. Being stunned completely disables the unit, but the effect is temporary since EMP damage decays over time. The decay rate is Health/40 per second, which is why it takes 40 seconds for a unit to drop from 100% EMP to 0%. Fractions of current health are unwieldy though, so it is time to stun some Jacks.\n\nA Jack has 6000 health, which means it heals 150 EMP damage per second. A Jack with 6600 EMP damage takes four seconds to decay down to 6000, so 6600 EMP damage corresponds to four seconds of stun. Note that most of the EMP damage required to stun a unit is spent reaching the stun threashold, with only a small amount needed to push the stun duration higher. If EMP damage could rise indefinitely then most units would end up with very long stuns, which is why each weapon has a limit on how much EMP damage it can deal over the health of its target, called the stun timer. Knight has a stun timer of 1 second, so cannot send a full health Jack beyond 6150 EMP damage.\n\nIn fact, Knights cannot deal EMP damage to anything on full health, simply because they deal both regular and EMP damage, and the regular damage is applied first. The old lightning weapons retained some of their regular damage when they gained EMP. The difference is shown by colour, with blue lightning dealing both damage types, while yellow lightning is pure EMP. Venom, the descendant of the TA spider tank, eventually gained a small amount of regular damage, so has some blue lightning mixed in. The order in which the damages are applied is important due to the interaction between EMP and health.\n\n

\n\nLightning weapons stun units by dealing EMP damage that accumulates on their target. This alternate damage type sits alongside health and is displayed under the main health bar. A unit becomes stunned when the EMP damage it has taken exceeds its current health. Being stunned completely disables the unit, but the effect is temporary since EMP damage decays over time. The decay rate is Health/40 per second, which is why it takes 40 seconds for a unit to drop from 100% EMP to 0%. Fractions of current health are unwieldy though, so it is time to stun some Jacks.\n\nA Jack has 6000 health, which means it heals 150 EMP damage per second. A Jack with 6600 EMP damage takes four seconds to decay down to 6000, so 6600 EMP damage corresponds to four seconds of stun. Note that most of the EMP damage required to stun a unit is spent reaching the stun threashold, with only a small amount needed to push the stun duration higher. If EMP damage could rise indefinitely then most units would end up with very long stuns, which is why each weapon has a limit on how much EMP damage it can deal over the health of its target, called the stun timer. Knight has a stun timer of 1 second, so cannot send a full health Jack beyond 6150 EMP damage.\n\nIn fact, Knights cannot deal EMP damage to anything on full health, simply because they deal both regular and EMP damage, and the regular damage is applied first. The old lightning weapons retained some of their regular damage when they gained EMP. The difference is shown by colour, with blue lightning dealing both damage types, while yellow lightning is pure EMP. Venom, the descendant of the TA spider tank, eventually gained a small amount of regular damage, so has some blue lightning mixed in. The order in which the damages are applied is important due to the interaction between EMP and health.\n\n \n\nThe inbuilt EMP systems offered by Spring have issues. The default stun threshold is based on maximum health, not current health. This works fine, but making EMP and regular damage completely independent wastes the potential of the system. There is a sweet spot where the disparate systems of a game exist in a loose web of interaction, not so tightly bound that the synergies become obvious, but just enough for people to find creative combinations. So in 2009 the CA developer SirMaverick added a way to use current health as the stun threshold.\n\nUsing current health as the stun threshold works well until you consider what happens when stunned units lose health. Say we have a healthy Jack on 6600 EMP damage, which corresponds to a four second stun. Then some Glaives come in to kill the Jack before it recovered, but they need not worry, since damaging the Jack would cause it to be stunned for longer. Indeed, if the Jack goes down to 4500 health in those four seconds, then it would still have at least 6000 EMP damage, giving it a stun of at least 13 seconds. This was a problem: we wanted some synergy between EMP and regular damage, not for EMP to become redundant after the first shot.\n\nThe escalating stun duration problem was solved by scaling EMP damage to changes in health. Consider a full health Jack with a four second stun. If the Jack suddenly dropped to 4500 health, then its EMP damage would be rescaled from 6600 to 4950. Stun decays at 112.5 per second at 4500, so the Jack retains its four second stun. This is why mixed regular and EMP damage weapons deal their regular damage first: to avoid instantly scaling down their EMP damage. The result is a nice push-your-luck interaction between EMP and regular damage. Do you spend your stun at the start of the battle to gain an early advantage, or risk waiting for some damage to be dealt first to go for a longer stun?\n\n